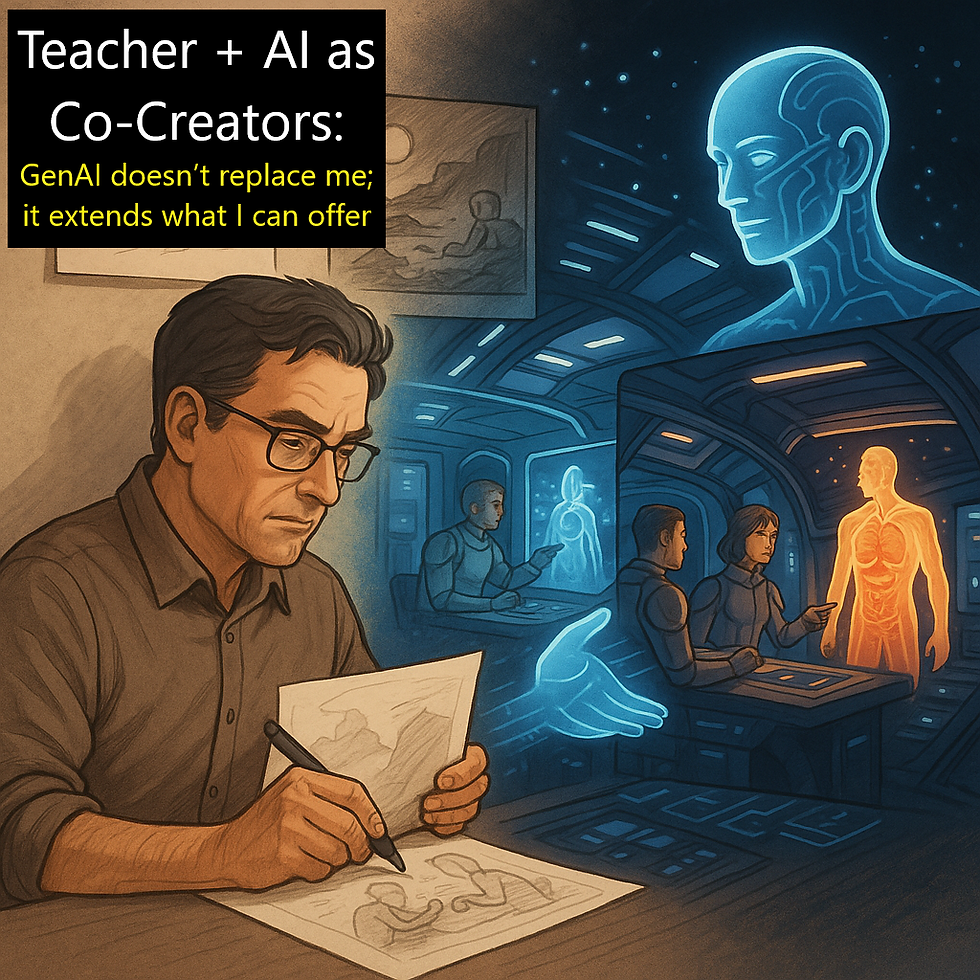

Teacher + AI as Co-Creators: GenAI doesn’t replace me; it extends what I can offer

- sasha97518

- Sep 22, 2025

- 5 min read

Hamish Fernando from the University of Sydney provides an example of how GenAI can be used to reimagine learning resources. By using AI as a co-creator, his own creativity can be turned into reality. Students take part in a long-running science fiction story, adding gamification to enhance the learning experience. Developing such a resource would normally be workload-prohibitive!

What if learning anatomy and physiology felt less like memorising a textbook and more like solving a mystery? That was the question I asked myself when generative AI tools first became widely available. Rather than fearing them, I saw an opportunity: here was a way to create kinds of assessments and activities I’d never have had the time or capacity to design alone.

AI doesn’t replace me as a teacher; it extends what I can offer. I set the framework and outcomes, and the tools help me build narrative depth, coherence, and detail that would otherwise take weeks of work. That means I can spend my effort making sure the science is accurate, the tasks are aligned to learning outcomes, and the puzzles really do push students to think.

Why I needed something different

I teach Human Biology to biomedical engineering students, many of whom come in with limited biology background. What is normally taught across four units is compressed into one. My goal isn’t encyclopaedic recall, but helping students see how the systems of the body connect—and showing that with fundamentals alone, they can already start reasoning through complex challenges.

In my lectures, I use Socratic discussion (my rule is: I won’t tell you anything you can work out yourself). This develops understanding, but there’s only so much we can do in limited lecture time. I needed an activity that let students apply their knowledge immediately, connect systems together, and see the payoff of careful reasoning. That’s where the story tasks came in.

What the biomedical story tasks are

Each semester, students take part in a long-running science-fiction story. They play the role of biomedical engineers stranded on a new world. Every week, a new chapter is released, and each puzzle can only be solved using the knowledge they’ve just learned. Sometimes it’s cardiovascular physiology, sometimes it’s musculoskeletal biomechanics, sometimes it’s respiratory mechanics—but always, the clue only resolves if they really understand the basics.

This isn’t “gamification for the sake of fun.” The story structure means they have to draw connections across systems, apply fundamentals critically, and build up to solving problems that feel complex and meaningful.

How AI made it possible

On my own, I could never have written the level of narrative detail these tasks demand. World-building, dialogue, puzzles, consistency across weeks—it’s simply too much on top of regular teaching. Together, GenAI and I act as co-creators. The GenAI provides a platform to extend my creativity and transform it into reality.

Here’s how I use AI to make it practical:

Just like we would expect students to use GenAI in an appropriate manner, such as the CAC Co-intelligence framework, so should educators.

Cognitive:

I set the outcome. For example: “Students should understand cartilage biomechanics in a low-gravity environment.”

I sketch a framework. What situation could force them to use this knowledge? Maybe colonists developing joint issues after prolonged exposure to zero-G.

AI:

Claude generates the draft. I use it to get an outline—plausible story beats, setting details, suggested events. ChatGPT then helps refine.

Cognitive:

Here’s where I polish: I tighten the pacing, making the narrative flow, checking the science, and making sure the clues line up exactly with what I want assessed. I remain in control, applying evaluative judgement and critical thinking.

The result is a narrative that is far richer than I could create alone. AI takes care of the bulk drafting, while I stay in control of pedagogy, scaffolding, and accuracy.

An example: Koolia Jo — Cartilage

One chapter asks students to investigate why joints are deteriorating so rapidly in a zero-gravity environment. They’re given short imaging descriptions, biomarker tables (like uCTX-II), and contextual details about the colony. To succeed, they need to explain how cartilage is normally maintained, why lack of load accelerates deterioration, and suggest what interventions might help.

The full chapter, Koolia Jo - Cartilage is available here:

How I keep it manageable for students

Low stakes. Each task is worth only 2.5–5%. This reduces pressure and makes students more willing to take risks.

Feedback first. The point isn’t to penalise small errors, but to highlight how their reasoning could be pushed further.

Flexible submissions. Students can submit as a short video, a mind map, or another structured format. That way, they can focus on their thinking, not a rigid format.

Collaboration encouraged. They can talk through the puzzles with each other, but the final submission is individual unless stated otherwise.

How you might try it yourself

If you want to adapt this to your own teaching, don’t start with a whole story arc. Begin with one scenario:

1. Write a single learning outcome you want students to apply.

2. Ask an AI tool to suggest a short story event where students could only progress by applying that outcome.

3. Generate the scene detail, then refine until the logic works.

4. Keep the task low-stakes, give feedback, and allow flexible submissions.

Even one “chapter” can shift students from memorising to reasoning.

Student feedback

Feedback was almost universally positive, my favourite pieces of feedback highlighting that it was a lot more challenging than quizzes but was so much more beneficial because it really got them to think more critically about their learning in order to apply it to the story context. I found that this allowed them to be more confident when preparing for exams, as they had already been thinking deeply about content all semester long

The evidence behind it

The research matches what I’ve seen. A meta-analysis shows gamification has a strong effect in science and engineering when narrative, mechanics, and dynamics are aligned (Li et al., 2023). Problem-based learning combined with game elements promotes critical thinking and engagement in engineering contexts (Čubela et al., 2023). Broader reviews confirm that gamification can improve motivation and learning outcomes, provided it’s carefully scaffolded and not just aesthetics (Castillo-Parra et al., 2022).

Closing thought

What AI gave me wasn’t less work—it gave me different work. Instead of spending weeks writing stories, I spend my time deciding what’s important to assess, refining the narrative, and making sure the puzzle really tests fundamentals. For students, it means they’re learning through play, but the play is anchored in science that matters.

Hamish Fernando

University of Sydney

22 September 2025

Comments